Why Stalker Should be Added to Your Christmas Watchlist

This article first appeared at Theopolis. Read it there HERE.

Stalker is a Soviet-era film by Andrei Tarkovsky in which an enigmatic location comes into existence either through an alien crash or a nuclear disaster; the film never makes it clear, but knowing Tarkovsky’s criticism of the spectacle nature of the alien motif after his own filming of Solaris and his inclination toward showcasing the hazards of dependency on technology, the latter is more likely than the former. The government has decided to blockade the area, known as the Zone. Guides who take people in and out of the Zone are called stalkers. If caught, they will be imprisoned. Such is the case with the hero of the film, an unnamed stalker who resumes his work as soon as he is released from jail, the point at which the film begins. For most people, the motivation for getting inside the Zone is to reach the place called the Room, which exists in the center of the Zone. When entered, the Room reads the innermost desire of the heart of the traveler and grants it. Those who make the pilgrimage often believe their stated desire to be their greatest desire. The truth or error of this assumption is not determined by the pilgrim but by the Room. This is one of the things that makes Stalker a kind of fable or morality tale, but it is not the only thing. Over the course of the film, the protagonist journeys from a place of seeking transcendence through escape to that of realizing its presence in the ordinary. It’s as though a prayer for the kingdom to come on earth as it is in heaven is being answered. The doctrinal center of the film moves from eschatology to incarnation.

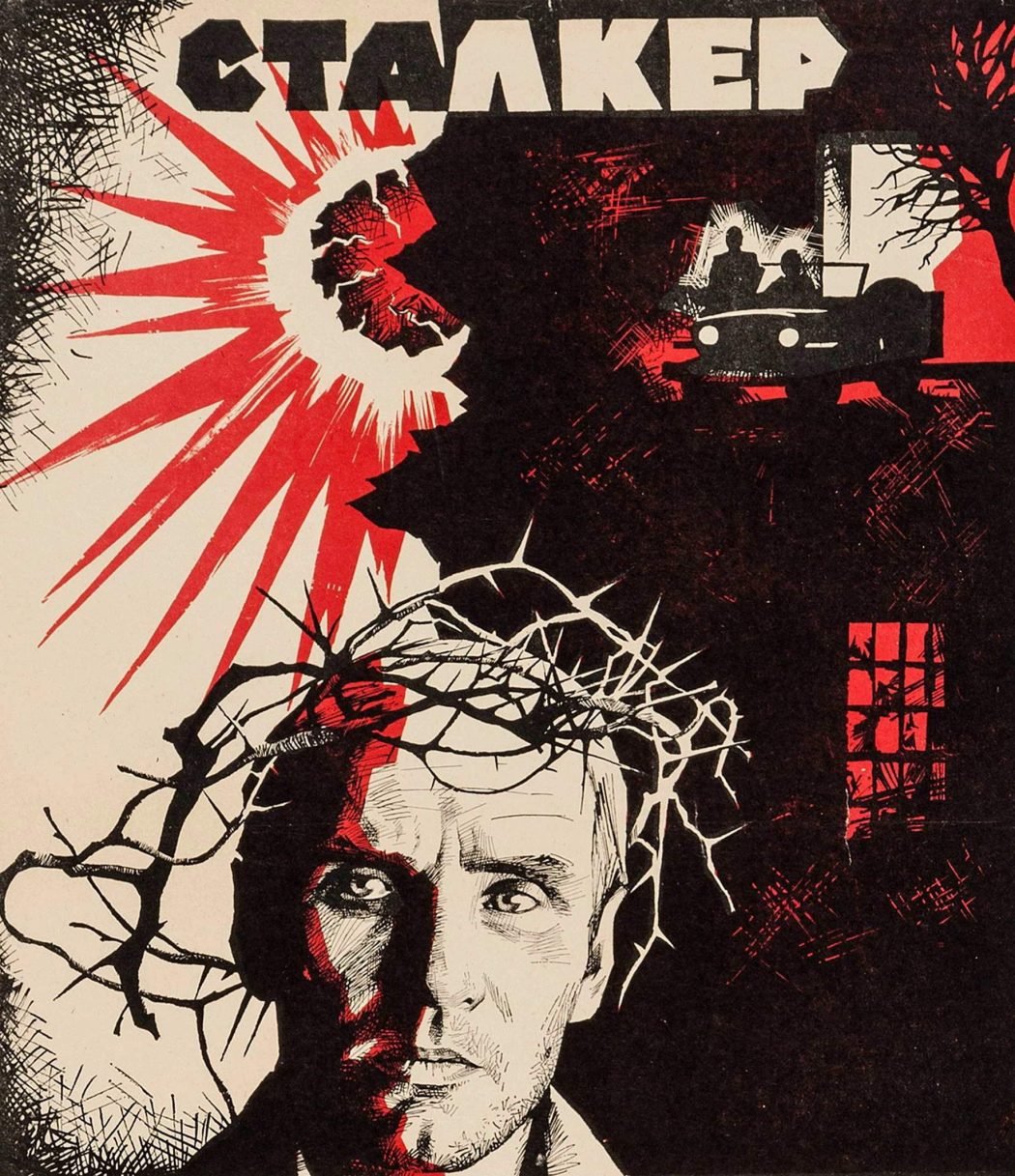

Shot in Estonia, Stalker debuted in 1979 as the final film to be created by the director within the borders of the Soviet Union. In this adaptation of a science-fiction novel called Roadside Picnic by Arkady and Boris Strugatsky, Tarkovsky lays a number of clues out for the audience that will encourage them to have not only the Christian faith in mind but specifically the work and person of Jesus Christ. Firstly, in the Soviet poster for the film, the stalker is seen prominently with a crown of thorns about his head. He embodies the sorrow of the Lord throughout as he mourns over the faithlessness of all whom he encounters. Tarkovsky, a Russian Orthodox believer, was forthcoming about his own Christian faith, stating that the central axiom of all of his films was the extreme manifestation of faith. Lastly, he uses large portions of Scripture in the script, including a scene in which the stalker is traveling with a writer and a professor (art and science), two men in search of the Room. In this scene the stalker quotes to story of the two disciples on the road to Emmaus who were unable to recognize Jesus until He was no longer with them. He ends the moment by asking the two pilgrims if they were awake.

Clearly, Tarkovsky’s Orthodoxy renders him fearless when it comes to creating access points to the transcendent within the structure of the ordinary. For some, however, it can be too much. Armin Rosen has suggested that Stalker marks the beginning of Tarkovsky’s directorial decline, due to the absence of genuinely human characters and the film’s tendency to lack urgency as it “drifts into the haziness of pure allegory.” It is possible, however, that the haze is there only as the stalker emerges from pure allegory, not that he wanders continuously within it. In addition, what some see as an absence of genuine humanity may be due to the absence of a humanity that is not haunted by the divine. A man haunted by a ghost is a different kind of man than one who is not. As the Athanasian Creed teaches, to be truly man does not necessitate that one be only man.

What makes Stalker such a great film to watch during Christmas is the unavoidable Immanuel- styled narrative arc. At the beginning of the film, the Zone is a kind of heavenly reality that one can only encounter by taking the long and treacherous journey of ‘crossing the line’. The emerging theme of the film is understanding glory in incarnation. The stalker is, at first, a kind of religious junkie, desperate for heaven in whatever experiential form it might take but desperate for it as an escape from the prison of the ordinary.

At one point, one of the pilgrims, the writer, makes the comment, “My dear, the world is so unutterably boring. There’s no telepathy, no ghosts, no flying saucers. They can’t exist. The world is ruled by cast-iron laws. These laws are not broken. They just can’t be broken. Don’t hope for flying saucers. That would be too interesting.” Keep in mind this is the pilgrim representing art not science. The artist, in a world with no transcendence, is no better than the neo-Darwinian lab technician. The writer accepts that there is no magic unless it has been fabricated to simulate meaning. The stalker, however, learns the lesson that not only is transcendence true, but its communication and interaction with the ordinary is real. Listen to the words of Athanasius:

The Word was not hedged in by His body, nor did His presence in the body prevent His being everywhere as well. When He moved His body He did not cease also to direct the universe by His Mind and might. No. The marvelous truth is, that being the Word, so far from being Himself contained by anything, He actually contained all things Himself. In creation He is present everywhere, yet is distinct in being from it; ordering, directing, giving life to all, containing all, yet is He Himself the Uncontained, existing solely in His Father. As with the whole, so also is it with the part. Existing in a human body, to which He Himself gives life, He is still Source of life to all the universe, present in every part of it, yet outside the whole; and He is revealed both through the works of His body and through His activity in the world.

The stalker, who is the first true believer we encounter, comes to realize over the course of the film that the power of the Zone is capable of existing simultaneously in both transcendence and immanence. He learns this, however, not merely on his own, but in many ways by growing in his understanding of what the existence of his daughter, Monkey, necessitates. She is a kind of child of the covenant. She is both a product of the Zone and of ordinary Russia.

All the film is in sepia, until the line is crossed into the Zone. The Zone is full color. This is important in understanding the Immanuel-styled narrative arc. In order to access full color, one had to leave the ordinary. After the stalker’s return from his journey, however, with the writer and the professor, something strange happens. Upon watching his wife and daughter from the front of the pub, he exits in order to join them. This transitions to the first full color scene that is not in the Zone. The camera is following Monkey, as she walks along the bank of the river. What is strange about this is that Monkey, due to the side-effects of her father’s time in the zone, is crippled. The viewer is led to believe, due to her ability to walk and the film’s recovery of full color, that she must be in the Zone. The stalker must have brought his family with him and they must live there now. Not necessarily. As the camera pans back and the wider angle emerges, it becomes apparent that what looked to be the movement of Monkey’s body as she walked is simply her body taking the shape and cadence of her father’s body as he walks while carrying her on his shoulders. This scene initiates the resolution of the incarnational trajectory.

Closer to the end, after this first entrance of color into ordinary life, the stalker is lying on the floor of his house, exhausted by the journey with the writer and the scientist. The color scheme is again sepia, apparently because Monkey is not present and she, in her youth and humility of brokenness, seems to be the key to understanding immanence. “If only you knew how tired I am,” the stalker says. “Only God knows. They call themselves intellectuals. Writers! Scientists! They don’t believe in anything. Their capacity for faith has atrophied through lack of use.” The stalker’s wife tries to console him. He wrestles with the thought that perhaps no one is worthy of the Room and his purpose and vocation are all for naught. It’s at this point that his wife offers to go to the Room and to seek something for herself, thinking this might comfort her husband. This only intensifies the horror for the stalker because it calcifies the reality that none are righteous — no not one. And so the final stroke is given. If the best of people are incapable of approaching the Zone on their own terms, then the only possible hope is for the Zone to approach them on its terms. And this is the clearly expressed desire of the director, to have the viewer believe that the Zone was not very far away . . . close by, even, if possible.

In Sculpting in Time, his manifesto on art, Tarkovsky says, “In Stalker, only the basic situation could strictly be called fantastic. It was convenient because it helped to delineate the central moral conflict of the film more starkly. But in terms of what actually happens to the characters, there is no element of fantasy. The film was intended to make the audience feel that it was all happening here and now, that the Zone is there beside us.” Zone with us, if you will.

In the final scene of the film, we see Monkey reading a book in the kitchen. The scene is in full color. The words we hear her meditating on in her mind are lines from the Russian poet, Fyodor Ivanovich Tyutchev. They call for the movement of one’s gaze to be fixed upon God in a posture of ascendence in order to cast one’s vision down and see the earth differently, as one changed by God.

I love those eyes of yours,

my friend Their sparkling, flashing, fiery wonder

When suddenly those lids ascend

Then lightning rips the sky asunder

You swiftly glance and there’s an end

There’s greater charm, though, to admire

When lowered are those eyes divine

In moment’s kissed by passion’s fire

When through the downcast lashes shine

The smoldering embers of desire.

She finishes the poem, closes the book and leans her head to the side while staring at a glass on the table. After a moment, the glass begins to move. Eventually, it slides across the entire expanse of the table and falls to the floor. Like the first introduction of color outside the zone, we are yet again led to believe something is miraculous rather than the truth that is deeply ordinary and thereby the miraculous nature of it is most likely lost on us. We are, at first, led to believe that Monkey is moving the glass telekinetically. The religious seeker wants it to be telekinesis. The prisoner of disenchanted realms is taught that Jedi Mind Tricks are the only magic worth imagining, but even the artist knows that they are not real. Not so the Christian. The Christian is given new eyes through which he or she is able to see the power of the transcendent pulsing in the very veins of the ordinary. Listen again to Athanasius:

It is, indeed, the function of soul to behold things that are outside the body, but it cannot energize or move them. A man cannot transport things from one place to another, for instance, merely by thinking about them; nor can you or I move the sun and the starts just by sitting at home and looking at them. With the Word of God in His human nature, however, it was otherwise. His body was for Him not a limitation, but an instrument, so that He was both in it and in all things, and outside all things, resting in the Father alone. At one and the same time this is the wonder, as Man He was living a human life, and as Word He was sustaining the life of the universe, and as Son He was in constant union with the Father.

We quickly learn that it was not with the power of the mind that the glass was moved, but the power of the physical encountering the physical through animated splendor. A train slowly begins to move closer and closer to the apartment until it is right on top of where Monkey is and the entire apartment is shaking in the gentle rhythm of the train’s cadence and movements. Regardless of what we thought about the movement of the glass, it was always the train.

Like everything worth celebrating during Advent and Christmas, Tarkovsky offers a vision of the Lord’s prayer being perpetually answered in the affirmative. The kingdom of God would come, not only on earth, but even within the confines of the Soviet Union, where clearly posted no trespassing signs were visible in every direction. The kingdom of God is on the move and it is moving towards those places that seem most devoid of Him. It must be on earth as it is in Heaven. There is no other way.

Just prior to the credits rolling, Beethoven’s 4th movement from his 9th symphony briefly plays in the background, but it is not part of the score. Having been empowered first by the gift of God, the singers offer back their ode to joy, but it bleeds in a muffled fashion into the kitchen where Monkey is seated with her head on the table, not dropped into the moment from the controls of the editing room as it were, but seeping through the walls from a radio playing in a nearby room.